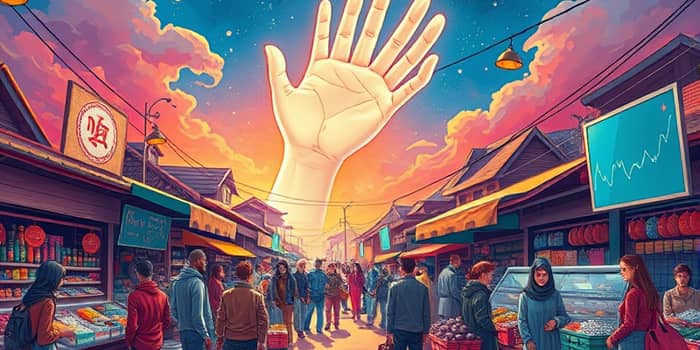

From ancient bazaars to modern stock exchanges, unseen forces shape our economic reality. Understanding the invisible hand can empower both individuals and policymakers to navigate complexity and unlock opportunity.

Historical Origins and Definition

In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, introducing the metaphor of the invisible hand. He described how individual self-interest and freedom could culminate in collective prosperity, without centralized direction. Earlier, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Smith laid the groundwork by highlighting how personal motives and local knowledge can produce unintended beneficial social outcomes.

Contrary to popular belief, Smith did not champion selfishness. He argued that ordinary decisions—driven by concerns for family, circumstance, and opportunity—aggregate into patterns that balance supply, demand, and production across society.

Mechanism: How the Invisible Hand Operates

The invisible hand thrives on three interlocking principles:

- Self-interest as a driving force: Buyers seek maximum utility at the lowest price; sellers aim for profit by cutting costs or innovating.

- Competition regulates behavior: Firms compete for market share, fostering quality improvements and price adjustments.

- Supply and demand dynamics: Prices shift to reconcile surpluses and shortages, guiding resources to their most valued uses.

Through this process, markets achieve:

- Market equilibrium: A state where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded.

- Efficient resource allocation: Capital, labor, and technology flow to high-return sectors.

- Division of labor: Specialization boosts productivity and innovation.

For example, if minivan production outpaces consumer demand, manufacturers face unsold inventory and lower profits. In response, they cut prices or shift output to more in-demand vehicles, restoring balance without government orders.

Real-World Data and Comparative Insights

Markets guided by the invisible hand have generated unprecedented wealth and innovation. Consider these figures:

Similarly, the S&P 500’s market capitalization, roughly 40 trillion dollars in 2025, reflects millions of decentralized investment decisions converging into a price-discovery mechanism. Each trade signals supply and demand for corporate shares, propelling capital toward higher-yield opportunities.

Criticisms and Limitations

Despite its elegance, the invisible hand rests on assumptions that do not always hold:

- Rational actors: Behavioral economics demonstrates biases, heuristics, and emotional decisions can distort market signals.

- Externalities: Pollution, climate change, and public goods often require collective action beyond private incentives.

- Monopoly power: When a few firms dominate, competition weakens and prices can deviate from equilibrium.

- Inequality: Market efficiency does not guarantee fair distribution; disparities can erode social cohesion.

Events like the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 shock revealed the need for targeted intervention. Unregulated credit markets and unchecked risk-taking can spiral into systemic failures.

Modern Debates: Balancing Markets and Government

Today’s policymakers wrestle with the tension between laissez-faire principles and strategic regulation. Advocates of minimal intervention stress that markets are the best allocators of resources over time. Critics insist that without guardrails, markets can exacerbate inequity and environmental harm.

Recent examples highlight both sides:

- Cryptocurrency booms showcase rapid innovation, but also rampant speculation and regulatory arbitrage.

- Global supply chain disruptions during the pandemic spurred calls for diversified sourcing and government stockpiles.

These debates underscore that the invisible hand is not omnipotent. Instead, it operates within a framework of rules, norms, and occasional interventions designed to correct market failures.

Applying the Invisible Hand: Practical Insights

Whether you are an entrepreneur, investor, or consumer, decoding market movements demands a nuanced approach:

- Observe price trends as signals of shifting demand and scarcity.

- Analyze competitive landscapes to identify emerging opportunities or risks.

- Consider external factors—regulation, technology, social trends—that can skew pure market outcomes.

- Stay alert to behavioral biases that influence your decisions and those of others.

By combining quantitative data analysis with qualitative judgment, you can anticipate corrections, capitalize on growth areas, and hedge against downturns.

Conclusion: Is the Invisible Hand Visible Today?

The metaphor of the invisible hand remains a powerful lens for interpreting market dynamics. It reminds us that decentralized decisions, guided by self-interest, can yield remarkable collective benefits.

However, real-world complexities—externalities, irrational行为, and concentrated power—mean that markets are rarely perfect. Recognizing when to trust market forces and when to call for intervention is essential for sustainable growth and equity.

Ultimately, the invisible hand is not a mystical force but a reflection of everyday choices. By understanding its scope and limits, we can better decode market movements and shape a future where individual innovation and social welfare advance hand in hand.

References

- https://longbridge.com/en/learn/invisible-hand-101008

- https://www.businessinsider.com/personal-finance/investing/invisible-hand

- https://www.britannica.com/money/invisible-hand

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invisible_hand

- https://fiveable.me/key-terms/ap-micro/invisible-hand

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53rKW8JRYhQ

- https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/what-is-invisible-hand/

- https://www.masterclass.com/articles/what-is-the-invisible-hand-in-economics